“The Best Years of Our Lives”: A Profound Tribute to the Sacrifices of War

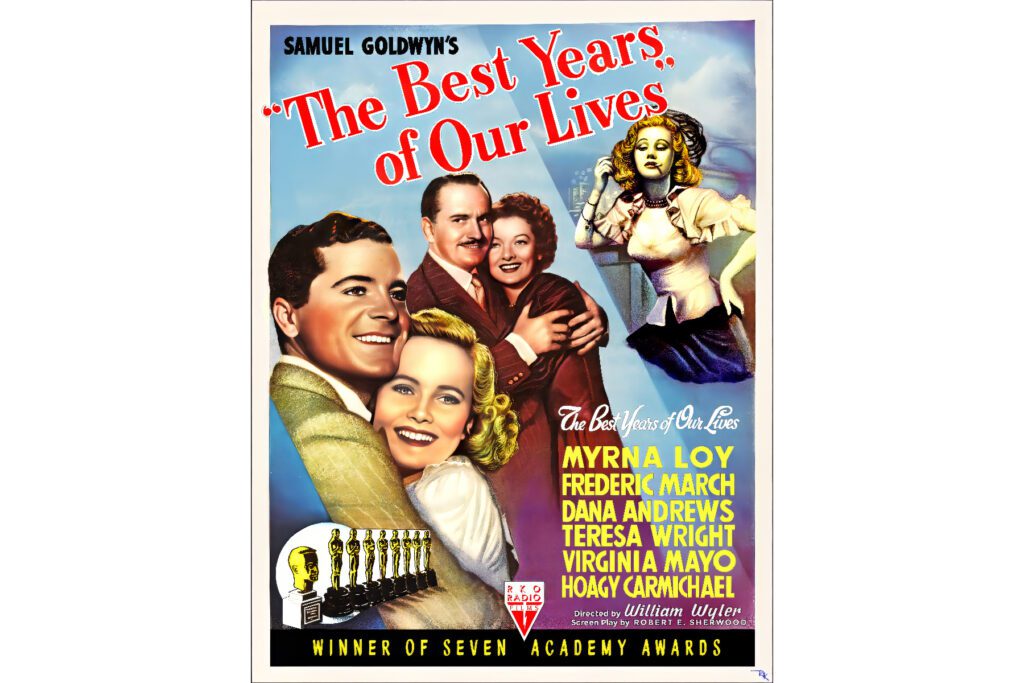

Released in 1946 to immediate acclaim, “The Best Years of Our Lives” remains one of the most emotionally resonant and socially powerful films to emerge from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Directed by William Wyler and based on a novella by MacKinlay Kantor, the film captured the raw, often invisible cost of war—not on the battlefield, but in the homes, hearts, and minds of the men who returned.

It swept the Academy Awards, winning seven Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Fredric March), Best Supporting Actor (Harold Russell), Best Screenplay, Best Editing, and Best Score. In an unprecedented moment in Oscar history, Harold Russell, a non-professional actor and real-life World War II veteran who had lost both hands in service, was honored twice for the same performance—Best Supporting Actor and a Special Academy Award “for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans.” To this day, he remains the only actor to receive two Oscars for a single role.

What makes “The Best Years of Our Lives” so enduring is its unflinching honesty. At a time when studios were eager to return to glamour and escapism, this film looked directly at the trauma, dislocation, and disillusionment that faced returning servicemen. The story follows three veterans—Al Stephenson (Fredric March), a banker grappling with changing values; Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), a bombardier facing unemployment and a failing marriage; and Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), a Navy man adjusting to life without hands and the quiet strength of those around him.

Rather than offer easy resolutions, the film explores the slow, painful reintegration into civilian life. Each character faces alienation, misunderstood trauma, and a society unequipped to deal with the psychological scars of war. PTSD is never named, but it lives in every hesitation, every drink, every distant stare. These were themes few films dared to tackle at the time—and even fewer did with such humanity and grace.

Wyler, himself a veteran who had served in the Air Force and lost hearing during combat filming, brought personal insight to the film’s moral weight. He insisted on authenticity in everything—from real sets to casting Russell—resulting in a tone that felt grounded, respectful, and deeply moving. The film also challenged American audiences to consider not just the sacrifices made abroad, but the responsibilities owed at home.

Nearly eight decades later, “The Best Years of Our Lives” still speaks with startling relevance. Its message—that coming home can be the beginning of a different kind of battle—continues to resonate with veterans and civilians alike. It’s not simply a war film; it’s a compassionate, unsentimental portrait of resilience, dignity, and the enduring cost of service. And in honoring that cost, it stands as one of the most important films ever made.